How to tap the Android screen from the underlying Linux system

In recent years phone screens seem to only have gotten bigger. This is great because it allows you to see more on your screen, but it also has some drawbacks. One of them has been very annoying to me: I can no longer reach buttons at the top left of the screen in a comfortable way.

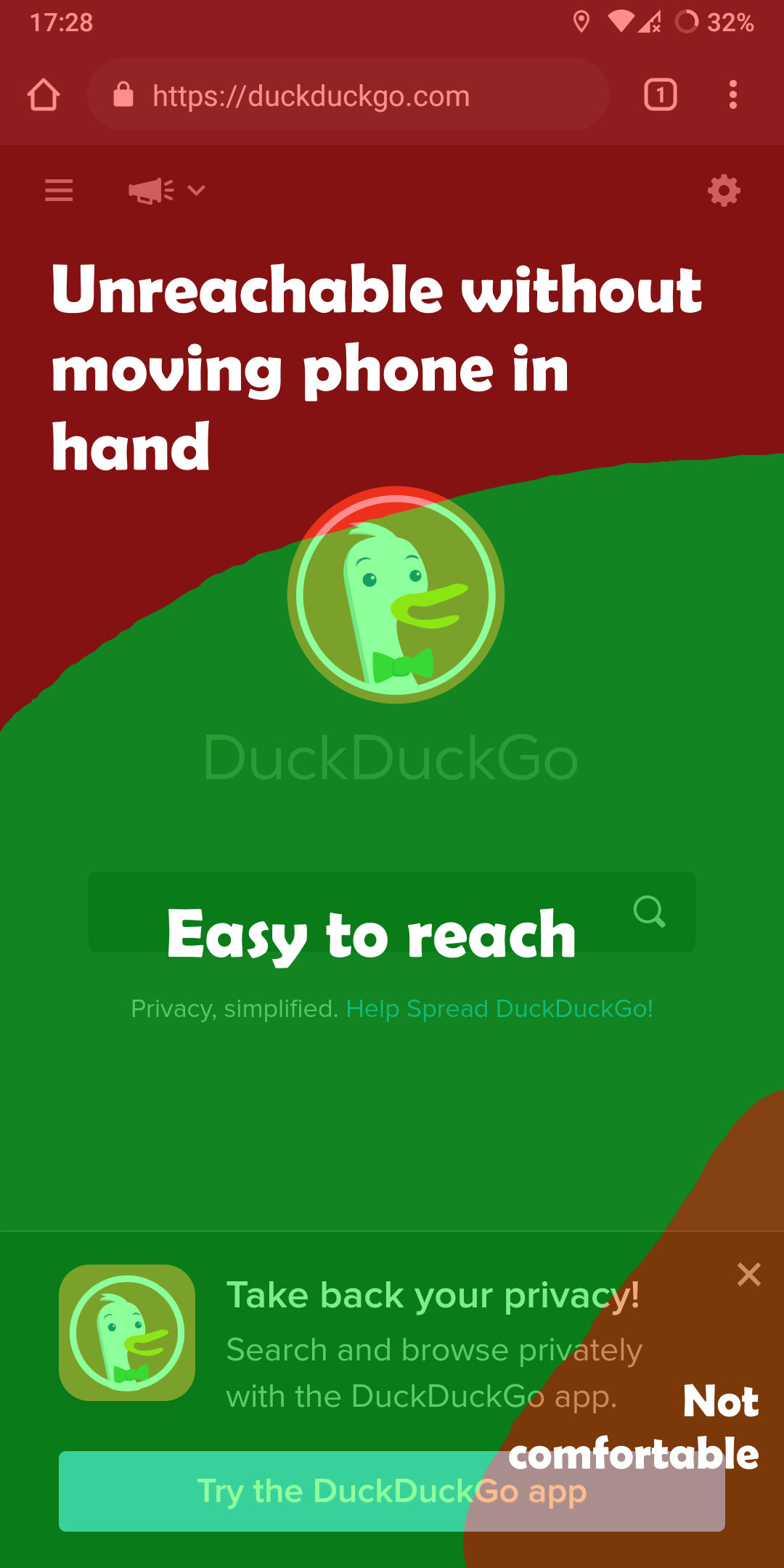

In a way, I would divide the screen in three areas:

- Easy to reach: the area can be reached with the thumb while holding the phone.

- Not comfortable: you can reach the area, but it’s not as comfortable as the previously mentioned one.

- Unreachable: this area is not in the reach of my thumb without repositioning my hand at the edge of the phone.

So to me the most annoying buttons are those at the top left. While those on the top right can still be reached with a little effort, the ones in the top left corner require more effort.

So how do we solve this problem?

The best way I came up with to solve this problem was a simple idea: What if there was a way to tap the top left corner without leaving the “Easy to reach” category?

My phone has a fingerprint scanner at the back that is very easy to reach. This scanner also doesn’t have any functionality when the phone is unlocked.

Detecting a finger on the sensor

So I took a look at the Android system log and found the following lines when putting the finger on and off the sensor:

fpc_fingerprint_hal: report_input_event - Reporting event type: 1, code: 96, value:1

fpc_fingerprint_hal: report_input_event - Reporting event type: 1, code: 96, value:0

The only relevant difference between these lines is the number at the end – 1 for “finger down”, 0 for “finger up”.

So that was easy – just write a program that scans the logcat output, detects these lines and then runs the input tap x y shell command to tap a specific point. Right?

No.

It’s so slow

The input command seemed very slow to me. It took quite some time from tapping the sensor to a reaction to the click. While testing it appeared to take at least 300ms, often worse with about 400ms.

According to a lot of anecdotal evidence, actions that take 100ms or less are perceived as instant. So this command definitely fails all expectations of “instant” (it was probably not designed to be fast, anyway). But why is that?

The “input” command

Android comes with a lot of different commands in /system/bin. Most of them are to be expected in a typical Linux environment (like tail, cat etc.) and some of them are specific to Android.

The input command, to my surprise, was just a shell script:

#!/system/bin/sh

# Script to start "input" on the device, which has a very rudimentary

# shell.

#

base=/system

export CLASSPATH=$base/framework/input.jar

exec app_process $base/bin com.android.commands.input.Input "$@"

If I read that correctly, it basically starts a Java program that can simulate a tap. There are also other actions it can do but for this post I don’t care.

Reducing the delay

One method to not have the long, noticeable delay is – quite simply – not relying on the input command. It just writes some data, that shouldn’t be too hard to copy. So instead of starting a script that starts a program that writes a small piece of data, we can just write it ourselves.

But what should we write and where should the data be written?

I don’t know exactly why, but I never really looked at the documentation (also this now makes a lot more sense) and started reverse-engineering this… open source protocol. Yea… anyway.

The first step when trying to reproduce a behavior is watching it. So how can we watch taps on the screen as they happen?

The getevent utility allows us to watch certain events happen in real time. It also makes it easy to list device files associated with those events.

Using getevent -pl (in a root shell on the phone) we can get a nice overview of devices, their events and device file paths:

chiron:/ $ getevent -pl

add device 1: /dev/input/event6

name: "msm8998-tasha-snd-card Button Jack"

events:

KEY (0001): KEY_VOLUMEDOWN KEY_VOLUMEUP KEY_MEDIA BTN_3

BTN_4 BTN_5

input props:

INPUT_PROP_ACCELEROMETER

add device 2: /dev/input/event5

name: "msm8998-tasha-snd-card Headset Jack"

events:

SW (0005): SW_HEADPHONE_INSERT SW_MICROPHONE_INSERT SW_LINEOUT_INSERT SW_JACK_PHYSICAL_INS

SW_PEN_INSERTED 0010 0011 0012

input props:

<none>

add device 3: /dev/input/event4

name: "uinput-fpc"

events:

KEY (0001): KEY_KPENTER KEY_UP KEY_LEFT KEY_RIGHT

KEY_DOWN BTN_GAMEPAD BTN_EAST BTN_C

BTN_NORTH BTN_WEST

input props:

<none>

add device 4: /dev/input/event3

name: "gpio-keys"

events:

KEY (0001): KEY_VOLUMEUP

SW (0005): SW_LID

input props:

<none>

add device 5: /dev/input/event0

name: "qpnp_pon"

events:

KEY (0001): KEY_VOLUMEDOWN KEY_POWER

input props:

<none>

add device 6: /dev/input/event2

name: "uinput-goodix"

events:

KEY (0001): KEY_HOME

input props:

<none>

add device 7: /dev/input/event1

name: "synaptics_dsx"

events:

KEY (0001): KEY_WAKEUP BTN_TOOL_FINGER BTN_TOUCH

ABS (0003): ABS_X : value 0, min 0, max 1079, fuzz 0, flat 0, resolution 0

ABS_Y : value 0, min 0, max 2159, fuzz 0, flat 0, resolution 0

ABS_MT_SLOT : value 9, min 0, max 9, fuzz 0, flat 0, resolution 0

ABS_MT_TOUCH_MAJOR : value 0, min 0, max 255, fuzz 0, flat 0, resolution 0

ABS_MT_TOUCH_MINOR : value 0, min 0, max 255, fuzz 0, flat 0, resolution 0

ABS_MT_POSITION_X : value 0, min 0, max 1079, fuzz 0, flat 0, resolution 0

ABS_MT_POSITION_Y : value 0, min 0, max 2159, fuzz 0, flat 0, resolution 0

ABS_MT_TRACKING_ID : value 0, min 0, max 65535, fuzz 0, flat 0, resolution 0

input props:

INPUT_PROP_DIRECT

It looks confusing at first, but especially the last device is interesting: It has all kinds of events that are associated with a multitouch device. That’s our screen. So now we know where to write data, the device file /dev/input/event1.

The question what we should write can be answered by watching the getevent -l output:

/dev/input/event1: EV_ABS ABS_MT_TRACKING_ID 0000504c

/dev/input/event1: EV_KEY BTN_TOUCH DOWN

/dev/input/event1: EV_KEY BTN_TOOL_FINGER DOWN

/dev/input/event1: EV_ABS ABS_MT_POSITION_X 00000037

/dev/input/event1: EV_ABS ABS_MT_POSITION_Y 0000008d

/dev/input/event1: EV_SYN SYN_REPORT 00000000

/dev/input/event1: EV_ABS ABS_MT_TOUCH_MAJOR 00000006

/dev/input/event1: EV_SYN SYN_REPORT 00000000

/dev/input/event1: EV_ABS ABS_MT_TRACKING_ID ffffffff

/dev/input/event1: EV_KEY BTN_TOUCH UP

/dev/input/event1: EV_KEY BTN_TOOL_FINGER UP

/dev/input/event1: EV_SYN SYN_REPORT 00000000

This is the output when doing a single tap in the top left corner of the display. Note that the numbers next to ABS_MT_POSITION_{X,Y} are the coordinates I just tapped. So the question is: how do we translate this? Not at all, we just remove the -l (“label event types and names in plain text”) option to get a more “raw” data stream:

/dev/input/event1: 0003 0039 0000504d # ABS_MT_TRACKING_ID

/dev/input/event1: 0001 014a 00000001 # BTN_TOUCH

/dev/input/event1: 0001 0145 00000001 # BTN_TOOL_FINGER

/dev/input/event1: 0003 0035 00000037 # ABS_MT_POSITION_X

/dev/input/event1: 0003 0036 0000008d # ABS_MT_POSITION_Y

/dev/input/event1: 0000 0000 00000000 # SYN_REPORT

/dev/input/event1: 0003 0030 00000006 # ABS_MT_TOUCH_MAJOR

/dev/input/event1: 0000 0000 00000000 # SYN_REPORT

/dev/input/event1: 0003 0039 ffffffff # ABS_MT_TRACKING_ID

/dev/input/event1: 0001 014a 00000000 # BTN_TOUCH

/dev/input/event1: 0001 0145 00000000 # BTN_TOOL_FINGER

/dev/input/event1: 0000 0000 00000000 # SYN_REPORT

OK, so that is the data. And we know where to write it. But still… how?

Let’s take a look at the source code of the sendevent command. It seems to basically be a lower-level version of the input command (not really, but still kind of).

The most interesting part is the input_event struct, which is filled with data and then written to a device file:

struct input_event {

struct timeval time;

__u16 type;

__u16 code;

__s32 value;

};

So before we had three columns with numbers in our output, and now we have three unsigned integers we want to fill with data: type, code and value. The getevent command outputs hex numbers, so we have to make sure we don’t accidentally use the wrong number format when specifying them in a program (definitely never happened to me…sure ;)).

Putting it all together

Now all we have to do is write the twelve events we observed previously in sequence to the device file and then test the program.

While implementing this is possible in any language, I chose Go for the task because of the ability to easily cross-compile from Windows to Arm64 Android. It also made it extra easy to define the events needed for a single tap:

// Define the input_event struct, but in Go

type InputEvent struct {

Time syscall.Timeval

Type EventType

Code EventCode

Value uint32

}

// Some const definitions, names are from the getevent output

type EventType uint16

const (

EV_ABS EventType = 0x0003

EV_KEY EventType = 0x0001

EV_SYN EventType = 0x0000

)

// Known event codes for a touch sequence

type EventCode uint16

const (

ABS_MT_TRACKING_ID EventCode = 0x0039

BTN_TOUCH EventCode = 0x014a

BTN_TOOL_FINGER EventCode = 0x0145

ABS_MT_POSITION_X EventCode = 0x0035

ABS_MT_POSITION_Y EventCode = 0x0036

ABS_MT_TOUCH_MAJOR EventCode = 0x0030

SYN_REPORT EventCode = 0x0000

)

// Value field of BTN_TOUCH, BTN_TOOL_FINGER

const (

TOUCH_VALUE_DOWN = 0x00000001

TOUCH_VALUE_UP = 0x00000000

)

// This event happens more often; marks the start/end of a sequence

var eventSynReport = InputEvent{

Type: EV_SYN,

Code: SYN_REPORT,

Value: 0x00000000,

}

// touch is the whole sequence of events that simulates a single tap

// While testing it seemed like not all SYN_REPORT events are necessary,

// but we will just use the same sequence as observed above

var touch = []InputEvent{

{

Type: EV_ABS,

Code: ABS_MT_TRACKING_ID,

Value: 0x0000e800, // Touch tracking ID, seems like we don't need to care about it

},

// Pretend to put the finger down

{

Type: EV_KEY,

Code: BTN_TOUCH,

Value: TOUCH_VALUE_DOWN,

},

{

Type: EV_KEY,

Code: BTN_TOOL_FINGER,

Value: TOUCH_VALUE_DOWN,

},

// Top left corner

{

Type: EV_ABS,

Code: ABS_MT_POSITION_X,

Value: 0x00000071,

},

{

Type: EV_ABS,

Code: ABS_MT_POSITION_Y,

Value: 0x000000a3,

},

eventSynReport,

{

Type: EV_ABS,

Code: ABS_MT_TOUCH_MAJOR,

Value: 0x00000005,

},

eventSynReport,

{

Type: EV_ABS,

Code: ABS_MT_TRACKING_ID,

Value: 0xffffffff,

},

// Now put the finger up again

{

Type: EV_KEY,

Code: BTN_TOUCH,

Value: TOUCH_VALUE_UP,

},

{

Type: EV_KEY,

Code: BTN_TOOL_FINGER,

Value: TOUCH_VALUE_UP,

},

eventSynReport,

}

Now we just write our sequence to the device file f:

// Assumption: f is the opened display device file /dev/input/event1

for _, ievent := range touch {

err := binary.Write(f, binary.LittleEndian, ievent)

if err != nil {

panic("writing input event: " + err.Error())

}

}

You can find the whole program here.

One interesting detail about the sequence is that it doesn’t always have to be the same. Sometimes, there are more SYN_REPORT events in a sequence, but interestingly they do not appear to change the result. According to the documentation, if no SYN_REPORT has been sent between two events, they are seen as sent in the same moment of time; so this event type acts as a separator.

Now that we have the code for a single tap, we can of course adjust the code to be able to tap any position by simply changing the x and y values.

In my tests this program has been a lot faster than the method with the input command, which was a nice outcome.

Actually using it

Now that we have done all the work to get a working tap program, we only need to integrate it into a program that detects the fingerprint press, then sends those events. I’ll spare you the details on that, you can see the whole program on GitHub.

It’s basically a daemon that runs in the background and detects the aforementioned log lines to react with a tap. It also has a few more commands, but they are not as technically interesting as the tap.

I also packaged the program into a Magisk (root solution with addons) module as that allows me to easily run it on boot.

Further ideas

One could use getevent and this method of writing events to create an event recorder that can accurately replay sequences of events. So if you want to automatically input a pin on the lock screen, that should be possible (the screen device file doesn’t have any restrictions on when the tap can happen, I think the input command is limited to an unlocked phone only, no lock screen access).

Thanks

If you found this interesting and want to create something like this or adapt the program for your phone, take a look at the repository.

If there are any mistakes in this post please feel free to point them out (by email, reddit etc.). Thank you :)

This post is also available on dev.to in case you want to comment there.